A Champion of the Telegraph - Charles Kraegen.

- Australia 1901-1988

- New South Wales

- Queensland

- South Australia

- Tasmania

- Victoria

- Western Australia

- International

- Special aspects

It is very difficult to glean details of ordinary people who did extraordinary things in the development of telegraphic communications in Australia.

One such person was Mr. Charles Kraegen.

The Ballarat Star of 23 February 1872 gave some background information:

Mr Kraegen was a native of Saxony - a generally well-informed man, and enthusiastically attached to all matters pertaining to telegraphy.

Mr Kraegen had formerly been employed in Ballarat under Mr Bechervaise as line-repairer and assistant. He was a good operator and took so large an interest in telegraph matters that he was recognised by Mr. Charles Todd, Director of Telegraphs for South Australia. In the early 1860s, Charles Kraegen left South Australia to join the department in Sydney. He was subsequently employed at the Telegraph Office at Albury and then at Deniliquin. He afterwards removed back to South Australia where, under Mr Todd, he was engaged in the arduous duties of forming the Overland Telegraph Line.

Appointment to Albury.

It is not known exactly when Charles was appointed to Albury.

The Albury Banner of 31 August 1861 noted that a group of seven men had formed the Albury Quadrille Assembly and Mr. Charles Kraegen was one of those men.

The Yass Courier of 27 August 1862 reported on the discussion in the Legislative Assembly on 1 July concerning the audit of the accounts at the command of Mr. Dunstan, a clerk in the Telegraph Department, six months prior to his absconding with public funds (no date for this malfeance was given). Charles Kraegen was listed as being one of five clerks in the Telegraph Department who had given security to the Government on or before the 1st June, 1862. Thirty four clerks had not given such a guarantee, In a strange twist, Mr Dunstan himself had been appointed to audit the accounts of the Money Order Branch. There was no imputation of wrong-doung by Mr. Kraegen.

In June 1867, Mr. Kraegen was asked to serve on the Committee for St. Mathews Church of England in Albury. Soon after, much of New South Wales was indundated by severe floods with significant displacement of families. The German community in the Colony - in Sydney, Albury and other places including Armidale, Goulburn, Berrima, Bathurst, Singleton, West Maitland, Orange, Yass, Gundagai, Wagga Wagga, Young and Deniliquin. Albury formed its own committee to help families and raise funds. The dedicated Charles Kraegen was one of the first to be included on that committee.

The Sydney Morning Herald of 1 November 1867 reported "The foundation stone of the new Telegraph Office was laid by Mr. Charles Kraegen, station-master, this afternoon, A large number of influential gentlemen of the town were present".

Appointment to Deniliquin.

In January 1869, Charles Kraegen was appointed Telegraph Station Master at Deniliquin. That was about eight years after the (first Government) Telegraph Office had opened there.

Deniliquin had quickly become the centre of many telegraph wires -

- from Echuca and Moama in the south;

- from Wagga Wagga in the east;

- from South Australia via Wentworth and Moulamein in the west;

- from Booligal and Hay in the north.

It was an important Repeater Station.

Typical effort of pushing the boundaries professionally.

In September 1869, according to the Riverine Advertiser, "Mr Kraegen, our telegraph station master at Deniliquin, lately succeeded in sending an uninterrupted message 2,700 miles direct on Tuesday evening last, a distance longer than the great Atlantic cable between Great Britain and America. The message was from Adelaide to Nebo, a distant station in Queensland. The feat recorded illustrates the admirable working of our Australian lines. Another message will be attempted in a few days over an uninterrupted wire of upwards of 3,000 miles in length".

The NSW Amalgamations.

The Pastoral Times of 8 January 1870 explained the implications of the amalgamations then being implemented across the NSW network. In part it noted:

"AMALGAMATION OF DENILIQUIN

POST AND TELEGRAPH OFFICES.

Pursuant to the intentions of Government, these offices were united on Saturday last and the Post and Telegraph Offices are now in the new and commodious building once designed for the Post Office.

The offices are under the superintendence of the Telegraph Master, Mr. Kraegen, assisted by Mr. Craig and Mr. Manners, both very active and very obliging persons.

Charles' world unravels.

March 1870: "DENILIQUIN TELEGRAPH AND POST OFFICES.

We regret to hear that Mr. Kraegen, who was in charge of these offices, has been suspended pending an inquiry into his conduct for neglect of duty, etc.

His child lay sick at Albury and Mrs. Kraegen had gone thither to see him. Mr. Craig, the assistant, had left for Melbourne and the line-repairer, Mr. Manners, was away repairing a fracture in the wire, so that Mr. Kraegen was left alone to attend the telegraphic and postal departments.

In the midst of his troubles, instead of keeping a cool head, he took to the bottle, as many others do in difficulties. Mr. Kraegen on Thursday week consequently was found unfit for duty. Telegrams of vast importance were remaining unsent and others were not received. A few of the prominent persons in the town telegraphed this state of things on Friday.

Mr. Olston, Station Master of the Moulamein, arrived on Saturday, superseding Mr. Kraegen, and a post-office assistant has since arrived from Sydney. We never remember the Sydney Government to act with such promptitude before.

Mr. Kraegen, who is a German, should never have been placed over both telegraph and post office, because he is not thoroughly acquainted with our language - and our native names of places, at times, puzzle well educated Englishmen. He is. however, about the best practical electrician and operator (so we are assured) in the service. We hope that he may be placed in a telegraph office where there is no post office and, in this hope, we are joined by all the respectable inhabitants of Deniliquin.

The fault is on both sides in this instance—first in the Government and then in Mr. Kraegen. With Government in particular, the first consideration in regard to its employees is to place the right man in the right place. Mr. Kraegen would be at home in any telegraph station where his now latent ability could be made more available".

Move to the Overland Telegraph.

The Albury Banner of 7 October 1871 reported "Mr. Kraegen, late of the Telegraph Office, Albury, is now stationed at Owen Springs, on the South Australian Transcontinental Telegraph line". Indeed it appears that he was employed since January 1871 as Storekeeper at Peake Depot. He was described as not being in good health, though somewhat improved since he had been on the Overland line. He was recognised as being an accomplished operator and electrician.

It is not known whether Charles actually obtained work at Albury - which given his dismissal is unlikely. He must have moved to Albury after his dismissal to be with his wife and sick child.

His sad end.

Wedged between news of the good growth of the wheat on the Murray and the prices of new wheat in the Hay Standard of 10 January 1872 is the one sentence announcement:

"It is stated that Mr. Kraegen, the telegraph official on the Northern Line, and who was formerly of Deniliquin, whose death was reported the other day, perished from want of water".

The Sydney Morning Herald on 13 January 1872 reported a full description of work and progress on the Overland Telegraph Line:

"On Wednesday, Mr. Todd received from Mr. Clark, the superintendent of the operators on the overland line, a telegram dispatched from the Alice Springs, where one of the interim stations is established, the spot being distant from Port Augusta rather over 900 miles ... It will be regretted that one of the first items of the despatch is the announcement of the death of Mr. Kraegen, one of the officials, whose strength proved unequal to the hardships end exertions he had necessarily gone through. The telegram was received on the morning of the 3rd January, on which day communication was opened between Alice Springs, in the Macdonnell Ranges, and Charlotte Waters, and thence on to Port Augusta and Adelaide.

The operators arrived at the Springs 28th December and waited there till communication was opened with Port Augusta. Messrs. Clark and Watson were to leave on the 4th instant, going northward. Mr. Kraegen was the operator who was to have taken charge of the Alice Springs station. During the erection of the line, he had been acting as assistant-storekeeper at the Peake depot. He was formerly station-master at Deniliquin, and was an accomplished operator and electrician. He appeared to have died from exhaustion on the journey, consequent upon his constitution not being able to bear the strain put upon it".

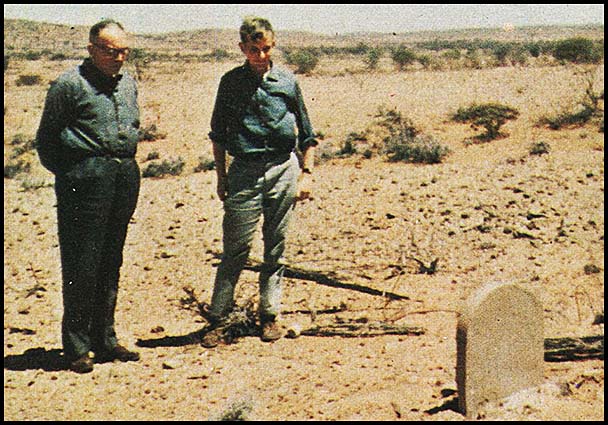

Charles Kraegen was buried and given a gravestone but his resting place was never recorded.

They discovered the grave of their family member in 1962. There is also a picture of this grave in the Sydney Morning Herald of 21 August 1972 showing a passing Camel Train. |

A correspondent of the S. A. Register, one of the party who nearly succumbed to thirst, gives detailed particulars of the disaster from which the following account is taken:

An advance party of three operators — C. W. Kraegen, J. F. Mullen, and R. C. Watson — was dispatched from Charlotte Waters on the 8th December to the new station posts in the desert, with written directions as to the watercourses they would find. In the evening, after a hot and exhausting day's travel, they came, says the writer, to a tree in a creek on which was read in letters punctured in tin and affixed there, the announcement that water was to be had at the junction of that creek and the Hugh, about a mile from that spot; the next water by the road ten miles or what we took to be such.

Off we sped down the creek. What to us was a mile of hot sand and pebbles now? We would have water in a few minutes and all would be well. We got to the place, looked at the hole, found it dry, dry; went down the Hugh in the hot sand and blazing sun, but gave that up and returned. We dug with hands, tomahawks, knives — we had no shovel - but still no water could be got, and the terrible disappointment made all now feel the want much more than would have been the case but for being assured by the punctured tin announcement that water was to he had thereabout ; besides the efforts in the scorching, white sand, walking in it to a depth of 6 inches, digging as far as our arms would reach, perspiring and choking, had thoroughly exhausted two of us to such an extent that we had to lie down and rest.

Then the question arose, "what are we to do?" After much debate, it was determined to follow up the channel of the Hugh, which took a course a little west of that followed by the road, and try for water at any likely spot. The proposal was made that as the pack-horse was in need of a spell, the saddle-horse that had succumbed before could now hardly travel, two of us were really knocked up, and as the water could not surely be over five or six miles off at furthest, the third man should take his own and the other comparatively fresh saddle-horse and with three water-bags proceed at his best speed. The proposition was jumped at.

Away he went, promising to be back soon and we meantime felt assured that the rest would serve the two tired horses that remained and enable them to go on after all had a drink. We waited, thirsted, and still waited through many hours of a very close, warm night, but still no water came and, as patience had run out when the moon rose, we packed up, and leading the horses started on foot after the messenger. It would be impossible to tell all the speculations made and discussed to account for his non-return. He had abandoned us! He had lost his horses! He had lost his way! But, horror of horrors, he had not found water! These and many other surmises arose, and none had any comfort in them for us who were now almost speechless and helpless for want of a drink.

We made little progress; the horses travelled slowly, and we had often to lie down, put our nostrils close to the ground, and thereby obtain a breath of comparatively cool air — a thing we could not get whilst walking. We wearied ourselves going to and fro, and although travelling much, did not go far, and so Saturday passed away. On Sunday we could hardly stir. My companion says I talked an awful lot of "bosh". I am sure he did — "gabbled" is the word — unintelligibly, and laughed occasionally, but somehow we managed to try again for water in the creek. It must be there — and so at it we went again on Sunday morning, wearing finger nails off and drawing blood from the fingers, until our want of success left but one resource — one horse might be shot and its blood would help us to make an effort to get on. We shot a horse — the weakest — and having got what we desired from that source, again sought the road and rested. We had a good supply of liquid now — a quart potful each — and might rest a little before starting and we did. How hot it was! The sun poured down upon us and I really thought we should never get over the plain; but we did. We sat and suffered. The poor horse crawled, and doubtless also suffered. He seemed to go at the rate of half a mile an hour.

On we crawled, until on rising a bank we saw the bed of the Hugh once more. The horse pricked up his ears, mended his pace, reached the steep rocky bank, and of a sudden (thank the Lord!) we saw water — a small pool 18 inches by 30 inches, and only a foot deep, but water. Down the steep hill we went, got off the horse's back somehow and simultaneously man and beast plunged into the blessed liquid to satisfy an appalling thirst that had lasted from 8 o'clock on Friday morning, 8th December, until about 2 p.m. on the Sunday following.

We rested the balance of that day, swigging water like a couple of dissipated fishes. On Monday, the 11th, we determined that as we could not go forward we would go back and meet the waggons. We led our horse and walked all the way. At the creek, we found that we had read sixteen for ten miles. We arrived at the Alice after walking through sixteen miles of sand, just in time to see some of the other party arriving from the opposite direction. They had found our pack-horse, but had heard nothing of our companion.

(23 February 1872).Finding Mr. Kraegen's Body.

One of the search party which was organised came on it at an angle-post about three miles from our camp and brought in his belt, found lying at his feet, and on which was his revolver, loaded all round, cartouche box and pouch. He left no scrap of writing, had no mark's about him; lay on his stomach, resting his head on the left arm, and holding his hat as if shielding his head from the morning Sun. His head was to the east, his face to the south, and not the faintest mark of a struggle appeared. He had evidently lain down exhausted, and quietly died for want of water nine or ten days before we saw him.

A grave was dug as near the spot as the stony nature of the ground permitted; and he was wrapped in a blanket and interred. Mr. Boucaut read the Church of England burial service over the remains, and caused a rough fence to be erected around the grave, against which bushes were placed to protect our departed companion's last earthly resting place from the native dogs. An inscription, punctured in tin, to the following effect, was attached to a stout board and fixed in place of a headstone:

" In memory of C. W. Kraegen, aged 40, who perished here for want of water, about 12 | 12 | '71. Buried 20 | 12 | '71.The camp was sad that night, and it has been so for many nights since for Kraegen was a favourite with all. He was a widower and leaves three children, now at school at Goulburn, N.S.W. Mr. Boucaut has by unanimous request taken charge of such property as he left here.

As a close to this sorrowful affair it may be stated that the two survivors, who had been with him shortly before his death, were very weak and ill when they rejoined the wagons. They were, however, as well provided for as it was possible under the circumstances and went on with the wagons on the 17th, on which day they revisited the Alice, where they camped for the night. Mr. Boucaut did all in his power to render the two as comfortable as could be managed, whilst the attention of Mr. Flint to the wants of the sick men deserves particular recognition".

(17 February 1872).

The Kapunda Herald of 2 February 1872 added further details:

"Kraegen was not at all experienced in bushman's life, and was unacquainted with horses. It is very unpleasant, as not long since his wife had died. He leaves two children (a boy and girl), at present in New South Wales, where he left his family on coming over to get on this line."

The South Australian Register of 13 February 1872 described:

"The Late Mr. C. Kraegen.

On Monday evening, an entertainment was given by some of our German fellow-colonists at the National Hotel, Pirie Street, for the benefit of the orphan children of the late Mr. C. Kraegen, a Telegraph Master, who died on the overland line while en route for his station. About 300 persons were present at the performance, amongst them many English people.

The programme opened with an overture spiritedly played by the Concordia Band. A lady then spoke an appropriate prologue. After this followed a one-act drama by Theodor Korner, entitled "Die Suhne". The dramatis personae, who were three in number, went through their parts with eclat, showing that they had thoroughly studied their task. After an interval "Love's Request", sung by an English lady, was so well rendered that an encore was demanded and, in response "Only" was sweetly presented. The "Sleeping Duet" from "Il Trovatore" was effectively given by two German ladies. Then the mirth-provoking "Sneezing Song" was produced by an English amateur who caused even more amusement by his rendering of "Nobody's Child". A duet from "Figaro" was excellently given and it was redemanded. The proceedings closed with a side-splitting farce called "Ein gebildeter Hausknecht" in which the performers acquitted themselves very creditably. The affair was decidedly successful throughout and, at the end, vociferous calls were given for the stage manager - but he did not appear".

Thanks for your service Charles. R.I.P.

Footnote: The Gazette of 4 June 1880 announced the appointment of Mr. Edward C. Kraegen, a probationer at Parramatta, to be a junior operator in the Head Office. It is not known if this person was one of the two offspring Charles left behind in Goulburn.